Prescribed Liberalism

Whitney Hubbs

Andrea McGinty

Shana Hoehn

Andrew Chapman

January 18 - March 12, 2022

Checklist

The process of normalization rejects examination in exchange for convenience. The works in this exhibition address a refusal to deny the reality of a world already possessed and the complicated, internal chance for freedom such clarity provides.

In this context 'Prescribed Liberalism' presents itself as a simple joke. Through prescribed ways of being and knowing based on social alignment, an intake of the world becomes a prediction. Denying the act of possibility and instilling an order of adherence, normalization presents a gauge that provides a short term formula hinged on strategies independent of any individual reality or true complexity. 'Prescribed Liberalism', used here as a simple moniker for the sake of an exhibition, declines order through continued, long standing inquiry into human desire, the process of aging, the devastation in the concept of America, and the mystery of the unknowable.

Each work in this exhibition reveals an open-ended curiosity towards life during a moment of deep polarization. A self portrait, or a sculpture created from household products, for example, becomes suspended in time based on conditions unique to its composition. A self portrait taken today is different from one taken next year, a household item in circulation now is a dated artifact by next season, and so on. Instead of creating art for an audience or appealing to the process of normalization through trend or ease of content, provided is a well-devised plan of escape constructed using elements of daily life revealing the theater of objecthood or the implication of historicism and its blind adaptation. It's through years of sustained inquiry in the same performance, the same materials, and the same narrative altering only slightly that allows for a clarity beyond prediction. Through this unique measurement each artwork herein replicates a personal agency that plainly "attends life and its possibilities" 1

Whitney Hubbs moved from taking pictures of other people's bodies (body doubles), to imagining objects as bodies, to self portraits. These photographs are imagined, produced, directed and captured alone without an audience in a makeshift studio space Hubbs maintained in Hornell, New York. Each image presents an effort of potential loss which could mean nothing at all as the audience does not exist, or everything as she actively challenges her own limitations. Hubbs finds freedom in the absence of the voyeur and conjures scenes based on the moralized concepts of shame, gluttony, invisibility, humiliation, humor and freedom.

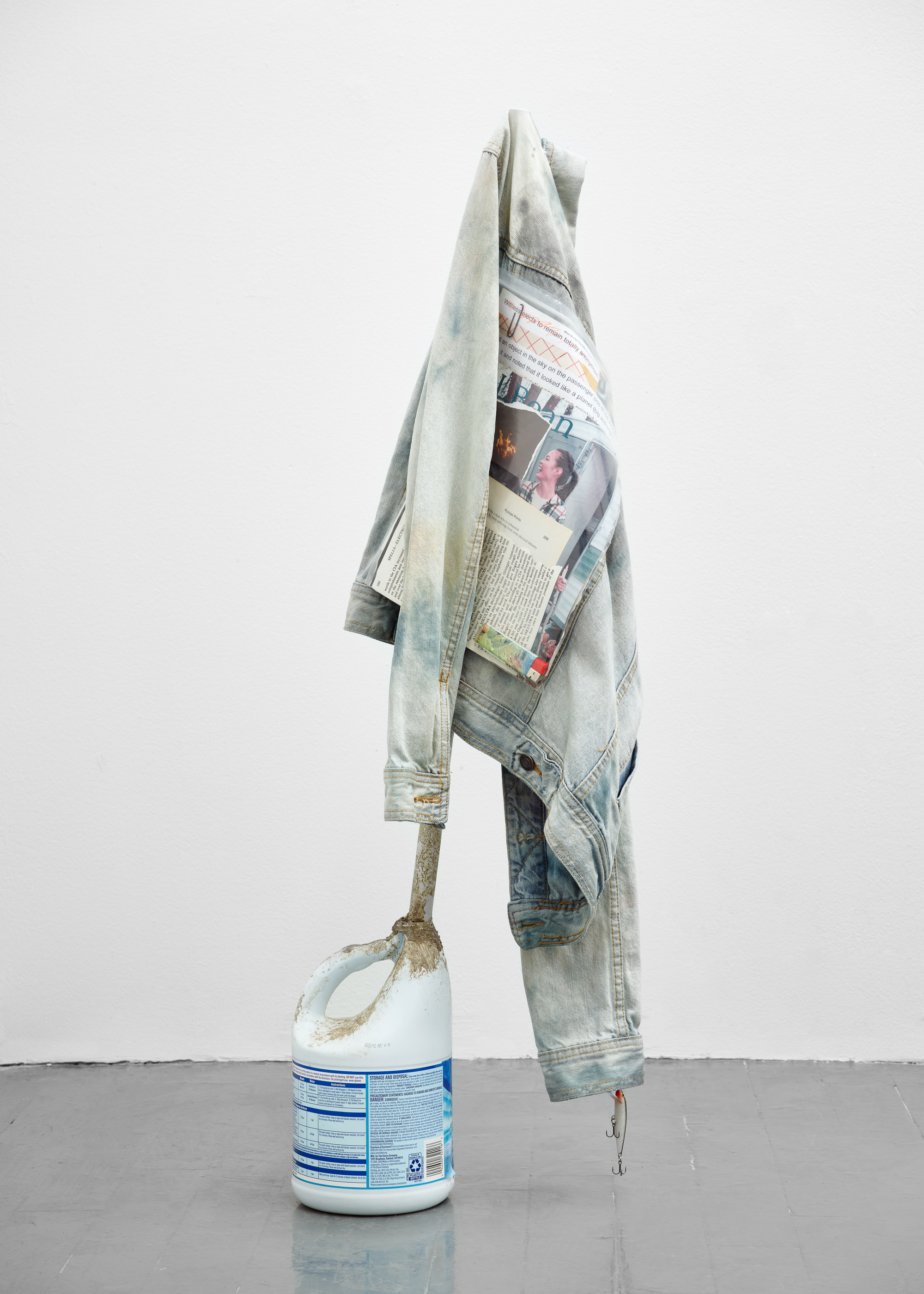

Andrea McGinty uses highly identifiable objects to create constructions related to concepts of home. Pairing scalable domestic carrier objects in precarious compositions, McGinty casts these domestic possessions as life-affirming models revealing their static state and potentially empty development. The energetic shell of these aspirational objects signal to each other, whether they come by way of ease (pourable cat litter), leisure (plastic lawn chairs, drink cooler, costumes), or false security (coyote decoy). The small flicker of hope lives plainly in the object's own availability and familiarity as a material placeholder for human desire.

Andrew Chapman approaches object making as a pure, material record of the unexplained. Rooted in painting, his work seeks to uncover what he calls a “photographic realism within abstraction.” Possessing both precision and chance through the cumulation of minute, calculated mark making, ‘Fulcrum (Nest)’ (2022) presents an image that is unsuspectingly rendered. The painting’s resolution subverts its happenstance appearance, pausing on the idea that the biographical data that permeates our physical world is simultaneously imbued with as much truth as it is mystery.

'400 years of digestion, serpent swallows ship' (2019) by Shana Hoehn begins with the replication of a Plymouth brand hood ornament, an object historically modeled after the Mayflower, taking the form of a serpent. Made of bronze and suspended mid-air, the tension between the serpent head and the breast wall mount captures the entrapment of our history 400 years in the making. The chilling exchange is irrevocably bound by a chain, highlighting an interdependence of the pursued and the pursuer.

—————-

1 Hsu, Hua, ‘What Normalization Means’, The New Yorker, November 2016

Installation

(Images: Michael Popp)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Individual Works

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Shana Hoehn

400 years of digestion, serpent swallows ship, 2019

bronze, steel

24” x 44” x 8” inches (60.96 x 111.76 x 20.32 cm)

unique

![]()

Whitney Hubbs

Chipotle 2, 2020

Polaroid

8 x 10 inches framed

unique

![]()

Whitney Hubbs

Andrea McGinty

Shana Hoehn

Andrew Chapman

January 18 - March 12, 2022

Checklist

The process of normalization rejects examination in exchange for convenience. The works in this exhibition address a refusal to deny the reality of a world already possessed and the complicated, internal chance for freedom such clarity provides.

In this context 'Prescribed Liberalism' presents itself as a simple joke. Through prescribed ways of being and knowing based on social alignment, an intake of the world becomes a prediction. Denying the act of possibility and instilling an order of adherence, normalization presents a gauge that provides a short term formula hinged on strategies independent of any individual reality or true complexity. 'Prescribed Liberalism', used here as a simple moniker for the sake of an exhibition, declines order through continued, long standing inquiry into human desire, the process of aging, the devastation in the concept of America, and the mystery of the unknowable.

Each work in this exhibition reveals an open-ended curiosity towards life during a moment of deep polarization. A self portrait, or a sculpture created from household products, for example, becomes suspended in time based on conditions unique to its composition. A self portrait taken today is different from one taken next year, a household item in circulation now is a dated artifact by next season, and so on. Instead of creating art for an audience or appealing to the process of normalization through trend or ease of content, provided is a well-devised plan of escape constructed using elements of daily life revealing the theater of objecthood or the implication of historicism and its blind adaptation. It's through years of sustained inquiry in the same performance, the same materials, and the same narrative altering only slightly that allows for a clarity beyond prediction. Through this unique measurement each artwork herein replicates a personal agency that plainly "attends life and its possibilities" 1

Whitney Hubbs moved from taking pictures of other people's bodies (body doubles), to imagining objects as bodies, to self portraits. These photographs are imagined, produced, directed and captured alone without an audience in a makeshift studio space Hubbs maintained in Hornell, New York. Each image presents an effort of potential loss which could mean nothing at all as the audience does not exist, or everything as she actively challenges her own limitations. Hubbs finds freedom in the absence of the voyeur and conjures scenes based on the moralized concepts of shame, gluttony, invisibility, humiliation, humor and freedom.

Andrea McGinty uses highly identifiable objects to create constructions related to concepts of home. Pairing scalable domestic carrier objects in precarious compositions, McGinty casts these domestic possessions as life-affirming models revealing their static state and potentially empty development. The energetic shell of these aspirational objects signal to each other, whether they come by way of ease (pourable cat litter), leisure (plastic lawn chairs, drink cooler, costumes), or false security (coyote decoy). The small flicker of hope lives plainly in the object's own availability and familiarity as a material placeholder for human desire.

Andrew Chapman approaches object making as a pure, material record of the unexplained. Rooted in painting, his work seeks to uncover what he calls a “photographic realism within abstraction.” Possessing both precision and chance through the cumulation of minute, calculated mark making, ‘Fulcrum (Nest)’ (2022) presents an image that is unsuspectingly rendered. The painting’s resolution subverts its happenstance appearance, pausing on the idea that the biographical data that permeates our physical world is simultaneously imbued with as much truth as it is mystery.

'400 years of digestion, serpent swallows ship' (2019) by Shana Hoehn begins with the replication of a Plymouth brand hood ornament, an object historically modeled after the Mayflower, taking the form of a serpent. Made of bronze and suspended mid-air, the tension between the serpent head and the breast wall mount captures the entrapment of our history 400 years in the making. The chilling exchange is irrevocably bound by a chain, highlighting an interdependence of the pursued and the pursuer.

—————-

1 Hsu, Hua, ‘What Normalization Means’, The New Yorker, November 2016

Installation

(Images: Michael Popp)

Individual Works

Shana Hoehn

400 years of digestion, serpent swallows ship, 2019

bronze, steel

24” x 44” x 8” inches (60.96 x 111.76 x 20.32 cm)

unique

Whitney Hubbs

Chipotle 2, 2020

Polaroid

8 x 10 inches framed

unique

Whitney Hubbs

Saran Wrap, 2020

Polaroid

8 x 10 inches framed

unique

Saran Wrap, 2020

Polaroid

8 x 10 inches framed

unique

Whitney Hubbs

Sarah Lucas, 2021

Polaroid

8 x 10 inches framed

unique

![]()

![]()

Andrew Chapman

Fulcrum (Nest), 2022

Acrylic on panel

18 x 16 x 1/2 inches (45.7 x 40.6 x 1.3 cm)

unique

Sarah Lucas, 2021

Polaroid

8 x 10 inches framed

unique

Andrew Chapman

Fulcrum (Nest), 2022

Acrylic on panel

18 x 16 x 1/2 inches (45.7 x 40.6 x 1.3 cm)

unique

Andrea McGinty

Clorox, 2021

hand-dyed denim jacket, plastic zip-top bag, mixed media, paperclip, lighter, Rapala fishing lure, flag pole, bleach bottle, concrete

41.5 x 16 x 8 inches (105.41 x 40.64 x 20.32 cm)

unique

Clorox, 2021

hand-dyed denim jacket, plastic zip-top bag, mixed media, paperclip, lighter, Rapala fishing lure, flag pole, bleach bottle, concrete

41.5 x 16 x 8 inches (105.41 x 40.64 x 20.32 cm)

unique