Koak

The Canary

September 8 - October 14, 2023

In 2020, thousands of birds dropped dead across the state of New Mexico. These included warblers, swallows, blackbirds, flycatchers and the western wood pewee. From the way the birds fell, it seemed that they had nosedived mid-flight during a seasonal migration.

No one knows why this happened. Smoke from a wildfire may have damaged their lungs. An extended winter could have disturbed their migratory pattern. Or maybe some mysterious celestial event occurred, causing every bird in the state to lose its will to fly.

This has happened before. Several times. In 1904, 1.5 million birds died in Minnesota, which is by the far the largest such event. Today, we look to these events as another chapter in the narrative of a shifting climate. At that time, the experience was considered an aberration, and was attributed to the unseasonal cold. A thousand years ago, the ancient Greeks used avian flight as a way to predict the future, through a practice called ornithomancy. An old world nursery rhythm counts magpies to foresee the vagaries of fate: “One for sorrow, Two for joy, Three for a girl, Four for a boy, Five for silver, Six for gold, Seven for a secret never to be told.”

When the artist, Koak was a child in East Lansing, Michigan she had lovebirds as pets. One died. Then another. Then another. This alarmed her mother, who eventually discovered that the house tested positive for urea formaldehyde insulation. The environment where they lived was inhospitable for birds, and yet, there they were, living in it.

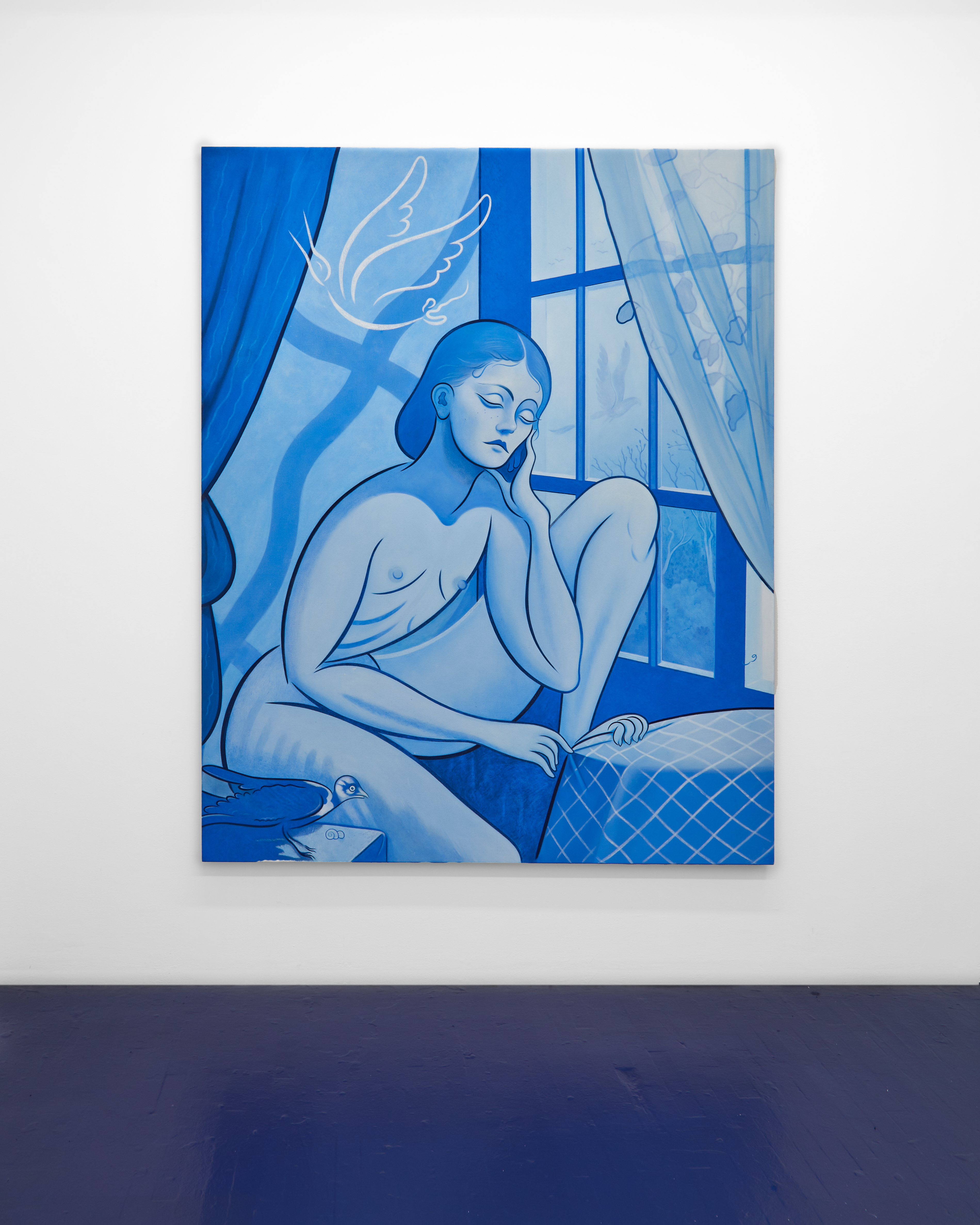

Historically, the canary has served this very function: a harbinger of doom. From the late 1800s until the 1980s, coal miners placed a caged canary in the mine where they were working, as a prophylactic. Due to their vast lung capacity, canaries were more sensitive to airborne toxins than humans, and would die long before the poison fumes killed any humans. Koak’s painting, The Canary is painted haunting flouro blue, a color that often appears when she is processing internal experiences. It’s almost a non-photo blue, a color used by comics artists use to sketch, because it cannot be perceived by the camera— a series of secret marks hidden in plain sight. As she painted her blue canary, Koak thought of anticipatory fears, the kind that we all spend our days anticipating — poor finances, ill health, cursed ecology, impending death.

Birds are the mythic symbol of mortality. Vultures pick at carcasses on the road. Owls wail when bad weather is coming. Poe’s raven caws an omen. Hitchcock’s crows flock to murder.

In the Rime of the Ancient Mariner, a sailor kills an albatross, a bird of good luck. Soon bad things begin to happen to him. In shame, he wears the dead bird around his neck as a reminder of his bad choices. Koak’s Albatross is a wild sea storm, reduced to it’s most refined forms. These waves and winds are terrifying. Here, in this place, mortality is fragile, and the possibility of its death hangs ominously overhead.

Swans are perhaps among the most elegant birds of death. The Ancient Greeks believed that swans are quiet most of their lives and sing most beautifully right before they die. This is why an artist’s final work is called a swan song, in hopes that they were saving the best for last.

Koak’s Swan is all puffed chest, in mid-inhalation, preparing for its exquisite melodic finale. This is “to let the breath fill the sculpture,” Koak writes, “from wings to toes, so that the focus isn’t post death, when the body has been transmuted to an object, but instead keenly in the moment of what must given up when we die—in the final energetic last throes of life.” This posture is a nostalgic one, nodding to the iconic Dutch painting, Still Life with Swan and Game before a Country Estate, in which a bird and hare have expired in a heap.

It’s a bittersweet artwork, something that must invoke surrender and wonder at once. This is fitting for Koak, who tells me “You can’t have sadness without joy.” These works are not mono-emotional. Here, in one sculpture, the chest is victorious while the legs hang in defeat. The ocean landscape is the same: a proud wave beneath a cruel sky. Even the human form in The Canary expresses this complexity: a spine curved in grief, a knee extended hopefully toward the sky, an expression as ambiguous as the human mind. Indoors, the human is caged; outside, the bird spreads its wings in flight.

Swan, albatross, canary — these are symbols borne from human fascination. They are, respectively, legend, art, and fact. We believe they are diviners, gliding in the direction of the future. They foretell the story’s ending; they warn us of inauspicious paths; and in the darkest pits of earth, they portend our own death. So we watch them closely. We are all birders, fascinated by the way these ancient creatures float through the heavens, free of earthly gravity. We look up and across the sky, chasing their movements with our eyes, hoping for answers in anything that is not ourselves.

-Ross Simonini

The Canary

September 8 - October 14, 2023

In 2020, thousands of birds dropped dead across the state of New Mexico. These included warblers, swallows, blackbirds, flycatchers and the western wood pewee. From the way the birds fell, it seemed that they had nosedived mid-flight during a seasonal migration.

No one knows why this happened. Smoke from a wildfire may have damaged their lungs. An extended winter could have disturbed their migratory pattern. Or maybe some mysterious celestial event occurred, causing every bird in the state to lose its will to fly.

This has happened before. Several times. In 1904, 1.5 million birds died in Minnesota, which is by the far the largest such event. Today, we look to these events as another chapter in the narrative of a shifting climate. At that time, the experience was considered an aberration, and was attributed to the unseasonal cold. A thousand years ago, the ancient Greeks used avian flight as a way to predict the future, through a practice called ornithomancy. An old world nursery rhythm counts magpies to foresee the vagaries of fate: “One for sorrow, Two for joy, Three for a girl, Four for a boy, Five for silver, Six for gold, Seven for a secret never to be told.”

When the artist, Koak was a child in East Lansing, Michigan she had lovebirds as pets. One died. Then another. Then another. This alarmed her mother, who eventually discovered that the house tested positive for urea formaldehyde insulation. The environment where they lived was inhospitable for birds, and yet, there they were, living in it.

Historically, the canary has served this very function: a harbinger of doom. From the late 1800s until the 1980s, coal miners placed a caged canary in the mine where they were working, as a prophylactic. Due to their vast lung capacity, canaries were more sensitive to airborne toxins than humans, and would die long before the poison fumes killed any humans. Koak’s painting, The Canary is painted haunting flouro blue, a color that often appears when she is processing internal experiences. It’s almost a non-photo blue, a color used by comics artists use to sketch, because it cannot be perceived by the camera— a series of secret marks hidden in plain sight. As she painted her blue canary, Koak thought of anticipatory fears, the kind that we all spend our days anticipating — poor finances, ill health, cursed ecology, impending death.

Birds are the mythic symbol of mortality. Vultures pick at carcasses on the road. Owls wail when bad weather is coming. Poe’s raven caws an omen. Hitchcock’s crows flock to murder.

In the Rime of the Ancient Mariner, a sailor kills an albatross, a bird of good luck. Soon bad things begin to happen to him. In shame, he wears the dead bird around his neck as a reminder of his bad choices. Koak’s Albatross is a wild sea storm, reduced to it’s most refined forms. These waves and winds are terrifying. Here, in this place, mortality is fragile, and the possibility of its death hangs ominously overhead.

Swans are perhaps among the most elegant birds of death. The Ancient Greeks believed that swans are quiet most of their lives and sing most beautifully right before they die. This is why an artist’s final work is called a swan song, in hopes that they were saving the best for last.

Koak’s Swan is all puffed chest, in mid-inhalation, preparing for its exquisite melodic finale. This is “to let the breath fill the sculpture,” Koak writes, “from wings to toes, so that the focus isn’t post death, when the body has been transmuted to an object, but instead keenly in the moment of what must given up when we die—in the final energetic last throes of life.” This posture is a nostalgic one, nodding to the iconic Dutch painting, Still Life with Swan and Game before a Country Estate, in which a bird and hare have expired in a heap.

It’s a bittersweet artwork, something that must invoke surrender and wonder at once. This is fitting for Koak, who tells me “You can’t have sadness without joy.” These works are not mono-emotional. Here, in one sculpture, the chest is victorious while the legs hang in defeat. The ocean landscape is the same: a proud wave beneath a cruel sky. Even the human form in The Canary expresses this complexity: a spine curved in grief, a knee extended hopefully toward the sky, an expression as ambiguous as the human mind. Indoors, the human is caged; outside, the bird spreads its wings in flight.

Swan, albatross, canary — these are symbols borne from human fascination. They are, respectively, legend, art, and fact. We believe they are diviners, gliding in the direction of the future. They foretell the story’s ending; they warn us of inauspicious paths; and in the darkest pits of earth, they portend our own death. So we watch them closely. We are all birders, fascinated by the way these ancient creatures float through the heavens, free of earthly gravity. We look up and across the sky, chasing their movements with our eyes, hoping for answers in anything that is not ourselves.

-Ross Simonini

Koak (b. 1981 in Lansing, Michigan, USA) lives and works in San Francisco, USA. Recent solo exhibitions include Altman Siegel; San Francisco, Perrotin; Hong Kong, Union Pacific; London, and Ghebaly; Los Angeles. Recent group exhibitions include Crafting Radicality at the deYoung Museum; San Francisco, I’ve got a feeling at Musées d’Angers; Angers, France,Heroic Bodies at Rudolph Tegners Museum and Statue Park; Dronningmølle, Denmark, and New Time: Art and Feminisms in the 21st Century atBerkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive; Berkeley, CA. Koak is a recipient of the Fleishhacker Foundation's Eureka Fellowship Award for 2020. |

The Canary, 2023

Flashe, signed and dated on verso

78 1/2 x 63 in.

199.4 x 160 cm

Swan Song, 2023

Bronze with silver nitrate patina

24 x 15 x 20 in. (plus 10 ft. hand-cast chain)

61 x 38.1 x 50.8 cm. (plus 3 m. hand-cast chain)

Edition 1/6 plus 2AP

The Albatross, 2023

graphite and casein on pearl grey rag paper

paper: 9 x 12 inches

framed: 13 3/4 x 17 3/5 inches